Chapter 7

Captive fruit flies demonstrate an oscillating population size in the absence of any change in room, lighting or nutrition.

The quarry here is an ancient enemy; it has been doing us dirt for longer than we have been human. The mechanism may take a few generations, but it can drive the birth rate right down to zero and keep it there.

An immediate challenge is whether this can be proven experimentally. The paper by Sibly I mentioned earlier showed that the mechanism, and he explicitly stated that there had to be a mechanism, is seen in mammals, birds, fish and insects. Of these, insects are so far down the food chain so-to-speak that just about nobody cares much about how you abuse them. I hasten to say that I never planned to and never did deliberately abuse my insects. How they felt about it all they never said.

The most popular insect for laboratory genetic studies is of course the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. They can be purchased cheaply; I got mine from North Carolina Biological Supply. My initial plan was to cross together flies that had been unrelated for a long time. The pleasant technologist I spoke with assured me that all the lines they kept had been there longer than the three years she had worked there. I bought sixteen lines of flies, one wild type and fifteen more each with a specific mutation, so the lines were unrelated for many generations.

Standard fruit fly husbandry dictates you start a new line with four males and four females so each time I crossed them I would take four males from one line and four virgin females from another. Calling the lines “a” through “p,” I crossed a with b to get ab, b with c to get bc and so forth until I crossed p with a to get pa. Then I crossed ab with cd, bc with de and so forth, so every generation I kept 16 lines going. Eventually I had lines abcdefghijklmnop, bcdefghijklmnopa and so on for 16 lines, each descended from each of the original 16.

It wasn’t so straightforward. Lines would die out, particularly after the first few generations, and my technique was not perfect. Sometimes a male would find its way into a vial of virgin females. I would have to go back and get vials that had gone according to plan. Sometimes I’d have to go back a couple or three generations.

My four generations never gave me complete infertility. I do not know what would have happened had I been technically able to carry it all out for five or six generations.

At this time, I released the flies in the final generation in a large cage:

The fruit fly cage.

Fig. 26

And you thought you had lab space limitations. I built on a base of a door using classical rabbit hutch technique. There was rather elaborate plumbing that let me vacuum out the cage or the pass-through although in the event I never used it.

Here is an inside view:

Inside the cage.

Fig. 27

Gloves were sewn into the walls of the cage so it was possible to reach in and move things without opening the cage to the outside. You can see flies flying about in the glare of the flash. The insects tracked green feeding formula over everything so the whole interior was rather green.

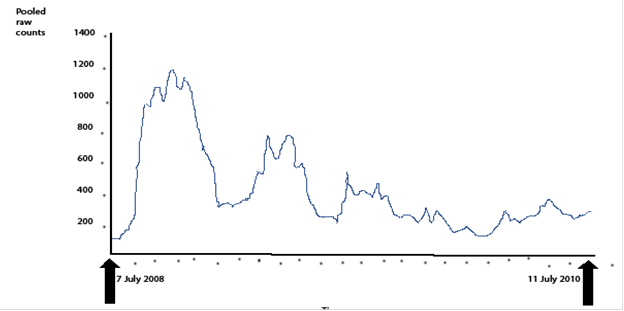

Each day I would add four new bottles and remove the four oldest, which had been in there for 28 days. I made daily counts at two measured windows and summed them at two-week intervals. The result was this:

Time course of population as reflected in raw daily counts pooled biweekly. The vertical axis is raw pooled counts. The horizontal axis is time.

Fig. 28 9

It is noisy, but you can see damped oscillation. You may also notice that each cycle shows a rapid rise and slow fall. Remember in the Sibly curve, when population falls – kinship rises – fertility rises quickly. When population is bigger than zero-growth – fertility falls slowly. I wish I could claim I had been clever enough to predict that would happen from the Sibly curve. Going back over it, that was probably not possible. There were four possibilities. The population might have been constant. There might have been stable oscillation between two population sizes. There might have been oscillation with increasing amplitude; this would be unstable and could result in loss of the whole population. And there might have been the damped oscillation we in fact see. Any of these could result from the Sibly curve so far as I see. Imagine the population near the zero-growth point and always attracted to that point. It might be expected to rock back and forth past that point.

Over the years of daily feeding and counting the fruit flies I would run across bits of fruit fly lore. For one thing, when a female deposits her eggs, she uses an internal device we call an ovipositor. When the ovipositor is extruded, she cannot have sex with a male. She has the choice; there is no forcing a female fruit fly. Feel free to relish the irony. Here we humans believe we have free will, and I should find it hard to contradict that, although we seem to exaggerate our power. We are quite willing to believe that other people have it, too, although I continue to caution. But I suspect a lot of us think of fruit flies as being small robots. They have such tiny brains. We can build a computer; oh, I don’t know how big and powerful the mightiest supercomputers are at the moment. It can weigh tons if you include the power to run it and the air-conditioning to keep it at operating temperature. And yet to date nobody has claimed to have got a computer to have free will; yet the fruit fly arguably does.

Two flies can be induced to fight if they are hungry enough and there is only one bit of food. Two males will fight over a female even though she has final say; it’s sort of a male thing, I suppose.

In order to win a female, a male will “sing” to her. He makes a buzzing sound audible to the human ear. He can sing in a staccato fashion and as simple tones. These are the two kinds of music I recognize as humans making – percussive and melodic. Are you feeling a bit more kinship with these tiny friends?

As a boy growing up in the South before the widespread use of air-conditioning, I have been pestered any number of times by gnats, house flies and mosquitoes. Once one has begun to torment you, you are in for a siege. But when I have had a fruit fly bussing around me ears, I have just waved it away. It departs, never to trouble me again.

Going back to the graph above, it seems clear to me that a female does not bestow her affection totally at random. She waits for Fly Right. Otherwise we should not see the damped oscillation. If you don’t agree, well and good. That’s just the way it looks to me.

Do they mate for life? I mean given the choice. In my initial breeding procedure, they were always forced to mate with strangers, and it seemed to work out well enough. I suppose they might somehow hook up as maggots and remember their sweethearts when mating season comes. If so, the male serenade must be something he picks up as an adult. Maggots may be able to do strange and wonderful things, but I don’t think singing is one of them.

A glance or a recollection back to the graph will assure you that the damped oscillation is manifested in peaks of decreasing height. But it looks like the troughs are also decreasing. Now I am baffled. Once more I have no intuitive sense for why this should be the case. We shall be on the lookout should it happen again.

There is another issue that puzzles me. If you look at later dates, after pooled count 77, the damped oscillation seems to stop. Is it setting up for another spike to be followed by another round of damped oscillation? I do not know, and I did not have sufficient curiosity to spend years more counting and feeding. What I did instead I shall go into later.

I think we can now draw some conclusions. You have the data, so feel free to make your own interpretation.

The speed with which changes occur indicate that this is an epigenetic process, not genetic. We have suspected as much, of course. For selection of genetic mutations to have a visible effect, reverse, reverse again and so forth has to take a very long time. We take epigenetic process or processes to be confirmed.

Yes, kinship governs fertility in fruit flies. Food and space were always ample. It was always in the same dimly lit room by day, dark by night, held at constant temperature so far as could be done by air-conditioning. The flies had a tranquil existence, only disturbed by the counting done at the same time every day, and by the regular feeding schedule.

Except for a few times over the years, counts were done by the same person. On the rare occasion when he was not available and I counted them myself, the numbers seemed a bit lower. I suspected they didn’t like me as much, swarming over the count window for the familiar face and sulking when it was only the old, fat one. I do not think the change was sufficient to throw the counts off perceptibly.

The mechanism gives the same result as would be expected from the Sibly paper. The population is, as it were, rolling back and forth across the zero-growth value. Do not get me wrong. When I say, “Would be expected,” that is not to say, “Was expected.” The damped oscillation was a complete surprise to me. I had figured that if I put an enormous number of flies together, they would mate at random and eventually die out. I promoted the scheme by moving the bottles around every day. I would remove one row of four bottles, move all the bottles on that side down, bring four bottles over from the other side, shove them up in the other direction and add four fresh bottles. We all know that fruit flies are extremely stupid. They would be expected to return to the same place in the interior of the cage and lose track of their home bottles.

Despite my dastardly designs, the flies never died out. Since their fertility depended on population size, and thus kinship, they practiced non-random mating. They did, indeed, keep track of the bottles. Stupid they might be, but this time they were smarter than I. It seems clear that the fertility of laboratory bred fruit flies is quite robust. It is also clear that you have to watch out for the little guys.

At the end of the day, we have done more than confirm that insects follow the Sibly curve, just as Sibly said they would. That would be success enough, but we have more. We have an experimental model with which to pursue an understanding of the mechanism. We shall be engaging in this pursuit later on, once in the cage and subordinate to that in a little side experiment. For now, just remember, fruit flies follow the Sibly curve, and they somehow or other recognize kin sufficiently to escape the outbreeding disaster we mentioned earlier.

Chapter 8

Table of contents

Home page